A Legacy that Learns

Regret grows when we isolate the past. But in a faithful community, even pain gains purpose. Our parents’ flaws weren’t fruitless—they helped plant the trees we now harvest. Legacy isn’t perfection—it’s generational perseverance.

Wrestling with the Past

I know a friend who was raised in a conservative Christian home. They love their parents—honoring them as the most sincere Christians they’ve ever known. And yet, they look back on their own journey—the prodigal path that led through relational brokenness, dead ends, and a whole lot of pain—and ask, What could have been different? What might have made it easier to trust God and stay the course?

Today, they seek to be a faithful child of God. And they’ll tell you that the very reason they turned back to Jesus was their parents—their faithfulness, their love, their example of a whole life devoted to Christ. But still, they carry mixed feelings. Deep regrets. Haunting questions. They look at our church community now and wonder, Why couldn’t my life have been more like the young people I see today? Why didn’t I have the same chances, the well-rounded experiences, the high school program, opportunities to serve abroad, the graces some now take for granted?

They harbor no blame. No hatred. No bitter desire to tear anything down. But there are honest questions. If we’ve changed so much . . . why didn’t we change sooner?

The danger in looking back is that we often compare the past to hypothetical ideals—imagined paths that were never tested, never dashed against the rocks of real people and life’s harsh realities. In 1921, Grantland Rice, renowned sportswriter and poet, penned a few verses to this effect that I find especially insightful:

Might Have Been

Here's to "The days that might have been";

Here's to "The life I might have led";

The fame I might have gathered in—

The glory ways I might have sped.

Great "Might Have Been," I drink to you

Upon a throne where thousands hail—

And then—there looms another view—

I also might have been in jail.

"Land of Might Have Been," we turn

With aching hearts to where you wait;

Where crimson fires of glory burn,

And laurel crowns the guarding gate;

We may not see across your fields

The sightless skulls that knew their woe,

The broken spears—the shattered shields—

That "might have been" as truly so.

"Of all sad words of tongue or pen"—

So wails the poet in his pain—

“The saddest are, ‘It might have been,’”

And world-wide runs the dull refrain.

The saddest? Yes—but in the jar

This thought brings to me with its curse,

I sometimes think the gladdest are:

“It might have been a blamed sight worse.”

The Danger of Oversimplifying

There’s a danger in looking back—especially when trying to trace the causes of our pain, our brokenness, or the outcomes in our life we don’t celebrate. The danger is in oversimplifying things—tidying up the past into neat little equations and, in doing so, losing our grip on reality.

Because when it comes to your family—your upbringing—there are layers upon layers of influence. It’s almost never one thing—one person, one failure.

First, there’s the ****human dimension. Your parents were human—limited in strength, in knowledge, in time. Imperfect people, perhaps trying to become what they themselves had never seen. And that humanity wouldn’t have disappeared if they’d raised you in a different setting. In fact, much of what frustrated you might have been even worse somewhere else.

My friend was raised in an imperfect home, within an imperfect community, but one that was committed to a higher vision—a shared pursuit of something greater, with more mutual support than most families ever experience today.

What if they’d been raised on the east side of Austin, in a neighborhood, in public schools? Do you imagine their parents’ weaknesses—their insufficiencies, blind spots, and failures—would have vanished? No. They would have remained. And likely, they would have been far more exposed, not less.

And then, there’s another layer to consider: What about your parents’ parents? Their own upbringing—the way they were mothered or fathered—were they trying to overcome deep wounds from their own past? Or were they building on a legacy of fruitfulness?

If we’re going to place blame on our parents, wouldn’t it be just as fair to blame the grandparents who shaped them? And what about the ones who came before them? Or should we stop and ask something else entirely: With all their faults and inadequacies, did our parents move the needle? Compared to their parents, was our experience more compassionate, more consistent, more submitted to the love of Christ?

But the layers don’t end there. What about the culture that surrounded your parents? What about their church family—or the intentional community they chose to raise you in? Or was it the broader atmosphere of modernity that you were brought up in, without ever knowing another path was possible?

How much of the burden belongs to culture itself?

If we’re speaking of an intentional culture, how old was it? How young? How tested? How proven? Were your parents pioneers—setting out from a place of brokenness, determined to find some solid ground of fruitfulness, but struggling through cliffs and crags and storms and torrents between where they began and where they longed to go?

The Risk of the Path Less Traveled

You might say, But I didn’t want to be an experiment. I didn’t want to be the side effect of my parents’ choices. And that’s real. That’s valid. But is that kind of risk only present for those who take an intentional path?

Or is it just easier to cast blame on the minority—the ones who dared to journey away from the mainstream toward the borders of a better life and future?

Because let’s be honest: parents raising children in the mainstream today are taking risks, too. They expose their sons and daughters to technologies and social influences the world has never known in prior eras—platforms whose long-term effects are still a mystery. Whose outcomes have never been tested on the scale we’re seeing today.

We act as if modern dating norms, social media, and the nonstop pulse of entertainment culture are the bedrock of American life. But for 2,500 years of Western civilization, these forces were entirely unknown. It’s only in the last 80 years—with the rise of television—and more radically in the last 15—with the advent of smartphones, social media, algorithm-driven feeds, and constant digital surveillance—that these previously unimaginable powers have begun to shape the minds, habits, and futures of entire generations. What we now treat as “normal” would have been unthinkable to every previous age.

Modernity is the experiment.

Tradition is the norm—if we can think beyond the bubble of presentism.

There is no love without the risk of betrayal.

No life without the risk of death.

No venture without the risk of failure.

No family without the risk of loss, devastation, or heartache.

And even in success, victory never comes without scars—without the bruises from the battles we fought and won. Or the mistakes we made—whose echoes still ring in the chambers of memory.

Everyone carries pain. Everyone. Hurt. Confusion. Anguish. Regret.

But the pain that is hardest to bear is the pain that seems to carry no meaning.

And this brings us to perhaps the biggest question of all:

What could give meaning to the failures of my parents—alongside their love and their successes?

What can turn my pain from blame into growth . . . into wisdom?

I propose an answer: a community of intergenerational faithfulness.

The Poverty of Individualism

Individualism strips generational flaws of their meaning. When someone views their parents’ faults as isolated to them, they tend to react—not heal. The pendulum swings, perhaps from authoritarianism to permissiveness, from over-control to neglect. The story becomes fragmented. Isolated.

The individual sees their life in pieces—memories, failures, dreams, and longings—without offering any of it to the shared reservoir of community wisdom and love.

And in that isolation, so much of what they’ve suffered seems to serve no purpose. No fruit.

But when you bind your life in covenant love to a multi-generational community—one mutually devoted and determined to push back the frontier and carve a path through the wilderness of confusion—then nothing is wasted.

Everything becomes a lesson.

A lesson without bitterness.

A lesson without blame.

A lesson without pride or anger.

A lesson that builds instead of tears down.

That prunes and grows and bears more fruit—fruit that remains.

Learning in Real Time

My own dear parents were unabashed about the fact that they were learning how to be godly parents. They had no standards in their own family tree—precious few examples to emulate. And they’d tell you plainly: they raised their middle children very differently from their first . . . and their last more differently still.

You live, and you learn.

But maybe, in the context of intentional community, you’ve felt that your parents were too strict. Too unyielding. After all, pioneering takes a certain kind of zeal and seriousness. Maybe their boundaries felt too sharp, too heavy-handed. But take a look at their children. Are their children—the second generation—raising the next generation with even more strictness? More rigidity? Less compassion?

Or are they building on what was right in the first generation while gently shedding the imbalances and carrying the lessons forward?

Fruit that Reveals the Root

If, in a multi-generational community, the second generation bears better fruit than the first, it’s not an insult to those who’ve gone before—it’s an honor. It testifies that the root was good, even if many branches still needed pruning.

And if the third generation draws even closer to the goal than the second, the second generation ought not to resent it. They should rejoice. Because they see that their mistakes and lessons learned didn’t die with them—they became wisdom for those who followed.

But let the later generations be careful not to lift themselves in pride and say, “Look how much better we are than our parents.” Because you wouldn’t even be without your parents.

The Sacrifice that Got the Wagon Moving

A 93-year-old brother, Mitch Parrish, once told me, “You know, I have a lot of respect for your dad—because of what he helped get started here.” And then he added thoughtfully, “It’s a whole lot easier to keep the wagon rolling than to get it moving in the first place.”

I’m grateful for growth and maturity—grateful for the changes and adjustments that God is still bringing about in our community and in our families.

Because, let’s be clear: if we ever become more devoted to our dogma than to our God—or to our children—we will fail.

Because the ability to correct course in humility is the very mechanism of life. And of flourishing.

Many of the incredible businesses and the alternative economy we enjoy as a people today were utterly unprofitable for the first several decades—not because they were mismanaged, but because they were, quite literally, impossible endeavors to begin with.

Our parents’ generation poured themselves out—as a sacrifice—into something from which they would never personally reap. Their only reward was watching us take possession of it, as it came of age, as it began to blossom and bear fruit.

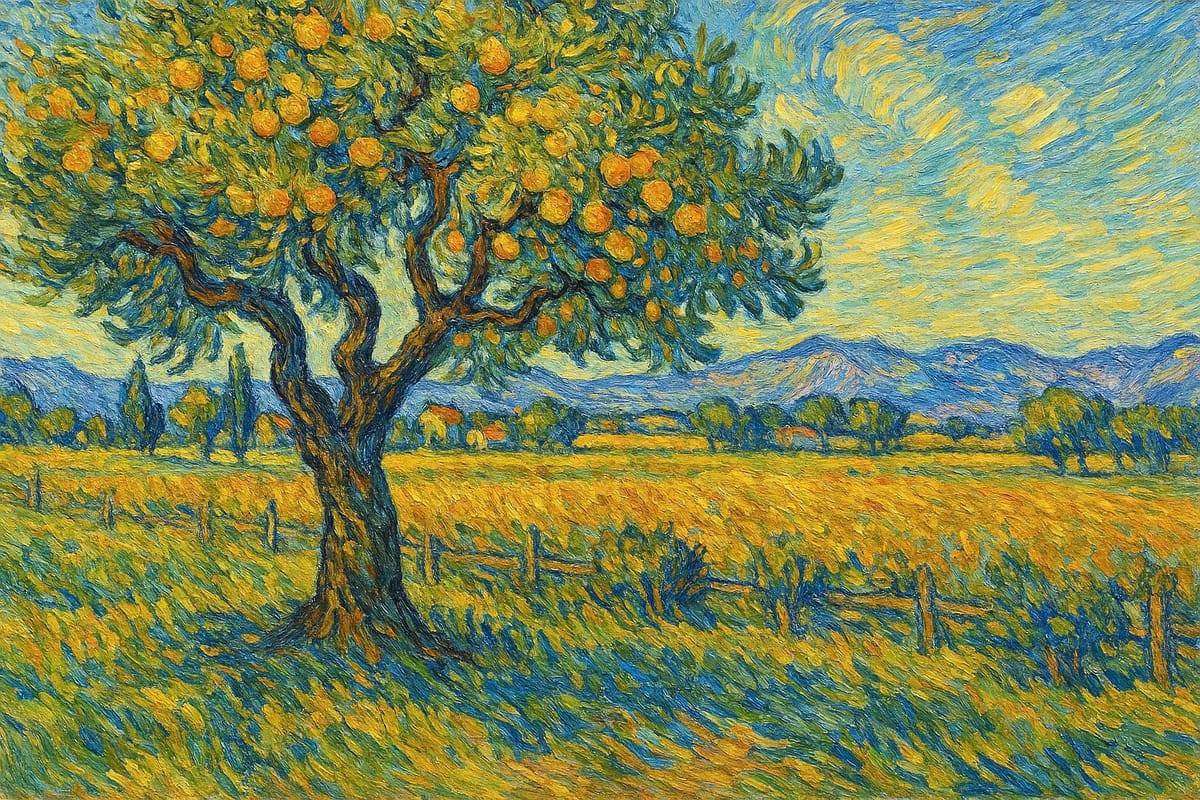

But let us not pluck from the trees planted twenty years ago and boast of our abundance. We didn’t plant those trees. We didn’t conceive of the vision. We didn’t take the agonizing, uncertain steps—those first, hardest steps—out of Babylon and toward the promise of a better life.

If I plant pecan trees today, they’ll only begin to bear fruit when my youngest, Ella, is having her first children. She could then look at those trees and say, “See, Dad—when they were under your care, they bore no fruit. But now, after just one year of my tending, the pecans are at last bountiful.”

And that would be laughably foolish—at least when it comes to trees. Pecan trees never bear for the first 10 to 20 years.

But it’s no less foolish when applied to a community . . . a vision . . . a dream . . . a way of life.

The greatest honor belongs to those who took the first steps—who made the first and most costly sacrifices. And if, in looking back, you realize that you hurt from some of their mistakes, don’t forget: you also received unimaginable blessings because of their decisions.

Don’t judge the tree by the actions, approaches, or perspectives that—like branches—have fallen away. Judge it by how, generation after generation, it continues to bear fruit that is bigger, sweeter, and more beautiful.

Say to yourself: My pain was part of the investment that revealed the right way, exposed the wrong way, and helped shape the grace I now see in the lives of these younger generations.

Look at how easy it seems for our youth today. Look at the doors open to them. Then say with humility: I paid for some of that. I bore part of the cost of learning, of struggling, of wrestling toward what we now enjoy.

And all these, having obtained a good testimony through faith, did not receive the promise, God having provided something better for us, that they should not be made perfect apart from us. Therefore we also, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which so easily ensnares us, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, looking unto Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith. —Heb. 11:39-12:2

A Good Tree

And remember the words of Jesus: A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, and a bad tree cannot bear good fruit.

But also remember: even good trees have bad branches that must fall, and even the good branches must be pruned.

And yet—year after year, decade after decade, into the second and third and fourth generations—the fruit is sweeter. More abundant. More beautiful than ever before.

Every branch in Me that does not bear fruit He takes away; and every branch that bears fruit He prunes, that it may bear more fruit. —John 15:2

So thank God—for placing you in the humble station of generational continuity. For giving you a role in a community of legacy.

Because in the end, it’s not about us.

We take credit for the faults, the shortcomings, the missteps.

He takes credit for the love.

For the joy.

For the peace, the patience, the kindness.

For the life He came to bring—

and that more abundantly.