Faith and Cabeza de Vaca's Miracle

This month, in November 1528, nearly 500 years ago, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his small, dwindling band of Spanish explorers staggered ashore on what is now the coast of Texas following a catastrophic shipwreck. They were the remnants of an ambitious expedition decimated by storms and starvatio

Shipwrecked on the Shores of Texas

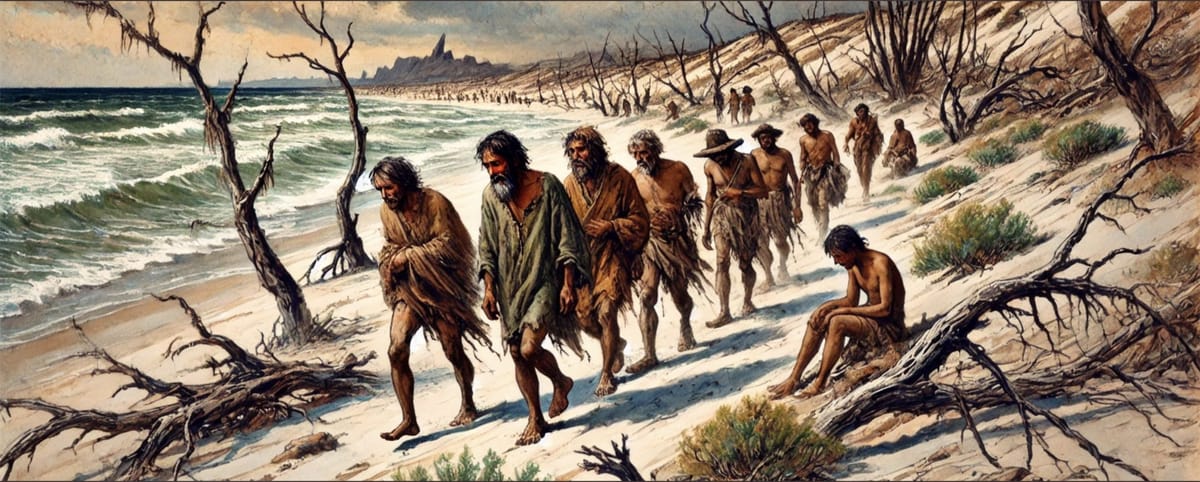

This month, in November 1528, nearly 500 years ago, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his small, dwindling band of Spanish explorers staggered ashore on what is now the coast of Texas following a catastrophic shipwreck. They were the remnants of an ambitious expedition decimated by storms and starvation. As they stumbled onto the cold, barren sands, most of their party had already perished. Only a handful remained to face an unknown world.

Stranded and destitute, they were reduced to foraging for roots and shellfish, scarcely enough to survive. The remnants of Spanish finery, now tattered and clinging loosely to their bodies, seemed almost mocking—pitiful remnants of a past life swallowed by the wilderness.

Captivity and a Desperate Prayer

But the wilderness had more in store. Soon after landing, they were taken captive by coastal Native American tribes. The natives looked upon these strangers with a mix of curiosity, suspicion, and hostility. And so began a new, harsher captivity, with little prospect of rescue or survival. Every day, death loomed closer, a constant shadow in their foreign exile.

Yet even in such desolation, faith took root. Desperation has a way of calling forth a new kind of hope, and in that brokenness, Cabeza de Vaca began to pray. One fateful day, a tribal elder lay dying, surrounded by his people. With nothing to offer but a fervent plea, Cabeza de Vaca knelt down, placed his hands on the man, and prayed for his recovery. To the astonishment of all present—especially the Spaniards—the man recovered.

Transformation Through Miracles

The tribesmen celebrated this as a sign of supernatural power, believing these strange foreigners held a divine gift. Cabeza de Vaca himself was as shocked as his captors. Later, reflecting on the experience, he confessed, “They wished to make us physicians without examining us or asking for our diplomas.”

In time, this unexpected moment of healing sparked a transformation. The natives, deeply spiritual and reverent of the supernatural, saw these Europeans as more than mere survivors—they were now healers, messengers of life from God. Cabeza de Vaca wrote, “During that time they came for us from many places and said that verily we were children of the sun . . . . We never treated anyone that did not afterwards say he was well, and they had such confidence in our skills as to believe that none of them would die as long as we were among them.”

Soon, Cabeza de Vaca found himself traveling from village to village. Native people began to follow him in massive throngs, bearing witness as he prayed over the sick. The sick found wellness; the despairing, hope. The chain of healing that began with a simple prayer over a dying man expanded until even the dead were said to be restored to life. He noted, “They brought us their sick, who, after we had made the sign of the cross . . . would say they were healed . . . . And at what the others whom we had treated told they rejoiced and danced so much as not to let us sleep.”

A Changed Man Returns to Spain

For nearly a decade, Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow survivors became woven into the fabric of tribal life. Then, in 1537, he finally returned to Spain, weathered by his years in the New World and forever altered by what he had seen and lived.

But home was not what he remembered. The cities of Christendom, once familiar and comforting, now seemed hollow. Vagrants lay unattended on the streets, the poor crowded into ghettos, and even the Church seemed distant from the pulse of compassion he had known among the tribes. Haunted by the disparity, he penned a letter to the king of Spain, conveying his dismay: “Our communal life dries up our milk: we are barren as the fields of Castile.” Spain’s bureaucratic, collective life seemed to have drained away individual initiative and compassion, leaving a society more barren than any desert.

A Thanksgiving Reflection for Today

Today, his words resonate profoundly. Like those distant cities of old, our society has increasingly turned to impersonal state systems to address needs that once called forth family, friends, and neighbors. But real charity, real compassion, demands presence and personal investment. To truly flourish, especially as the church, we must reawaken the compassion within us, learning to answer needs with love and presence rather than deferring to distant systems.

As Jesus taught, “It is more blessed to give than to receive.” When we delegate to institutions that God entrusted to family, church, and community, we forfeit the opportunity to deepen our souls through service. As we reflect on our blessings this Thanksgiving, may we also heed Cabeza de Vaca’s journey—not by dwelling solely on our comforts, but by reaching out, rekindling compassion, and offering our hands in love.

May we relearn the rare virtue of caring deeply, giving selflessly, and serving wholeheartedly, reviving that forgotten fire of faith that once healed nations and moved mountains.