Horses, Highways, and Holy Encounters

After 3,100 miles in an RV, we found far more than scenery—we found communion, courage, and quiet revival. From horse-drawn buggies in Wisconsin to barefoot farmers chasing bears, the slow pace of real life invited our hearts to see again. Here’s some slow-crawling, soul-healing good news.

Dear friends,

Rebekah, my mother, the kids, and I made it home this Tuesday evening, and by Wednesday morning, it was off to the races—high school classes, assignments, and evaluations approaching for all grades. It felt as though we had never left stride. And yet for two weeks, we had lived in a completely different rhythm.

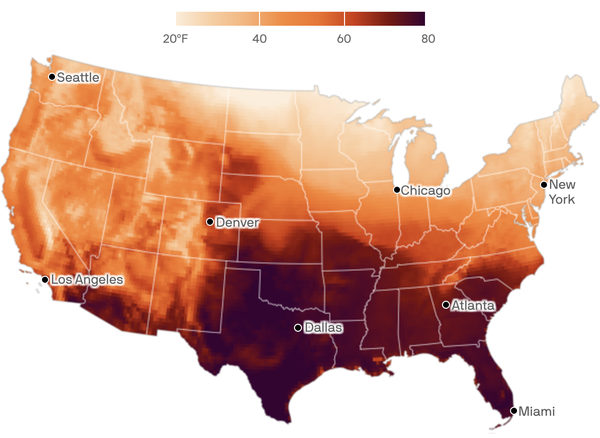

We were living out of a camper—all nine of us. Aside from a rebellious fridge door that kept dislodging during travel and spilling its contents on the floor, and one solitary flat tire, the RV adventure was mercifully uneventful. My trip odometer read 3,100 miles and indicated exactly 65 hours of driving since embarking from our home. But the real measure wasn’t in the miles. It was in the conversations, the stories, the encounters, the prayers. I spoke, taught, listened, and learned. I marveled again at the diverse wonder of the church—the body of Christ emerging in so many unexpected places.

As I began to write this letter, I thought of the many journeys I’ve taken over the past decade and a half to strengthen churches and believers scattered across the world. So many times, I’d write home to my dad, aiming always to squeeze jumbled thoughts into glimpses of glory—moments I knew he’d rejoice in, knowing he’d pass them along to the family and often to the whole congregation. But now he’s been gone four years this week. In some ways, it feels much longer. In others, only yesterday.

It’s not the grand gestures of a loved one that you remember most—it’s their kind presence, the smile across the room, the lilt in his voice when he’d answer the phone and sing out your nickname to some ditty he’d hijacked from a 40s song. Time cannot erase what love has etched on the human soul.

Truth is—life’s brightest moments can feel dimmer when there’s no one to share them with. We humans are sharers above all: we haven’t fully experienced a thing until we’ve shared it with someone we love. We meet someone special, and the experience fully blossoms only when we tell someone already special to us. A gift, a personal triumph, a miracle—and we instinctively reach for the phone, burst into words, and in the telling, our joy merges and compounds with theirs to become a rejoicing large enough to hold all that effervescent wonder.

So though I can’t call my father anymore, I’ll pour some of those feelings out here instead. And maybe, for those who need a smile or a spark of encouragement, you can help carry this load of good news with me.

They say bad news flies while good news crawls. But here’s some slow-crawling, soul-healing good news.

A Slow Ride, a Slower Gift

I keep pondering our visit to Wisconsin—the breathtaking contrast of cultures colliding and somehow harmonizing. People from California and all manner of other places, often shaped by a culture of so-called “freedom,” hedonism, addiction, and image, sharing life with families who had never driven a car until recently, nor barely touched a cell phone. They were raised at a pace that most of us have forgotten exists.

Saturday evening, after another farmhouse feast of heaping portions of food and fellowship, we stepped into the cool twilight (yes, the Texas-like heat does break in the evenings). There in the gravel driveway stood two horse-drawn buggies, harnessed and ready. Our drivers, John and Joel, took the reins and ushered us into an entirely different frame of mind and awareness.

You cannot miss how much more of the world you perceive at that pace. You hear the birdsong. You notice the sway of clotheslines and the shimmer of water in the brook. The world, in its rightful speed, invites the soul to sponge in its breadth. The slowness is not a burden. It’s like a peaceful prayer.

At times, our driver would whistle or hum. My children say Joel would even pull out a harmonica and play along the route (though I missed that ride). But these were no amusement park rides—it was a living rhythm, passed down from generations of boys and men who’ve gathered and fed animals, stitched and oiled harness, and worked the land longer than they can remember. And you can feel it. The conversations, the presence, even the eye contact—everything had a different weight.

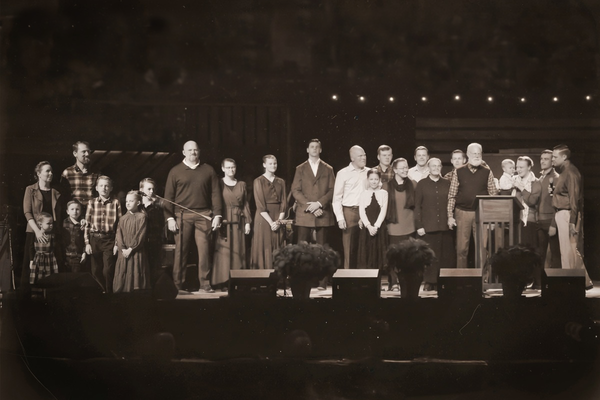

We were humbled again and again by the kindness, honor, and hospitality of the whole Wisconsin fellowship. They made us feel seen, remembered, welcomed, honored. But we kept repeating it to them: we felt like the ones who came away rich.

The Bear in the Cornfield

One morning, we piled into a 15-passenger van and rode through the verdant valleys. John and his wife, Ruth Ann, were strategically placed in the middle so that all could hear his stories, often seeming as if from another world, another rhythm. We passed draft horses plowing rows, cows waiting patiently near barns, and laundry waving like soft flags—whites, blues, yellows, and blacks.

He told us how Amish children are given a list of birds—hundreds of species—to spot and identify in the wild. A rare sighting will send buggies rolling in from all directions. They share their discoveries without phones, without texts. Word spreads by heart, by habit, by heritage.

Then John spoke slowly, without drama, almost too calmly, “Sometimes . . . we have a rare sighting of a black bear. And that brings everyone out.”

He pointed across a gently rolling pasture. “One Sunday, we spotted a black bear in this very field. The road right here was lined with black buggies. Everyone was in black—it was Sunday.”

He continued, “A bunch of us men went out and surrounded the bear. We made a sort of human corral and started pushing him back this way . . . toward the women and children.”

You could hear the pause in our breath. The modern mind panics. “Toward the women and children?!”

But John was unfazed. “The bear made it almost to the road . . . then broke ranks. Took off that-a-way.” He gestured toward the woods. “Another man and I chased him down. I got in front of him, waving my hat in his face. He was throwing his head, foaming at the mouth. He was mostly bluffing. But I started to think I was about to become his lunch.”

Eventually, John gave up and retreated. “At least,” he shrugged, “we tried.”

No wink. No embellishment. Just the plain truth—corroborated by others in the van. And you wonder—how could these gentle, pacifist farmers stare down a bear when most of us would scramble up a tree at the first glimpse?

And the answer sinks in: they haven’t been shaped by other people’s myths. They haven’t swallowed dramatized danger, horror films, or news cycles of dread. Their reality is shaped by the land, by storms, by animals, by ancestors and daily toil. Their courage is carved from contact with reality.

And I found something beautiful in that. A fearless farmer, eyes clear, spirit soft. A man in touch with God’s creation and image-bearers alike, raising children who will meet life’s trials differently than we were trained to.

They live without running water. They use an outhouse. They haul their water in and out. And yet, somehow, they exude a peace that often eludes those of us with hot water on tap and HVAC on demand.

We’ve been trained to run—from pain, from hardship, from anything uncomfortable. But sometimes the fear is the real monster, not the thing it warns against. Sometimes, freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.

From California to Calvary

I wish I could write much more. I wish I could tell you the personal stories—of young couples and middle-aged parents, many from California, learning to be fathers and mothers for the first time. I wish I could paint the picture of families coming back together, of addictions broken under open skies, of a young man lying on his back, staring at the stars, praying through the night until something breaks—and he rises at dawn with tears on his cheeks and no more desire for the drugs, no more thirst for the bottle, no more need to return to the madness he left behind.

The faces in that fellowship will stay with us. Some lifted toward heaven, arms outstretched, tattoos marking where they’ve come from—symbols inked in green, wounds inked in memory. Others bear the weathered calluses of a life spent on the land. But all of them—every last one—beamed with the same joy, the same fraternity, the same unifying freedom that comes from being found in the body of Christ.

I’m not trying to claim this is the only expression of Christ’s body. There are many. But we are so profoundly blessed by this one. And I pray these reflections stir something in your own heart—something grateful, something awake, something willing to question what you’ve been trained to fear . . . and bold enough to discover that hardship, faced together in grace, is not something to escape but something to transform us.

Yes, the Amish heritage holds much to admire. The discipline, the simplicity, the family cohesion. But there’s a sadness, too, that so much beauty is shadowed by fear—by threats of rejection, by rules that replace relationship, by trust in human structures rather than the Spirit of grace. Their barns and buggies may differ, their clothing and customs may seem strange, but in the end, it is not color or form that makes a life holy—it is the presence of God, dwelling in His people, knitting hearts together in mercy and love and truth.

So I leave you with this: the beauty of a barefoot farmer chasing a bear through a cornfield . . . the laughter of children riding buggies past blooming clotheslines . . . the tears of a former addict breaking free beneath the stars . . . and the stillness of a mother, standing by a wood stove, whispering thanks to a Savior who sees.

May we all be bold enough to step outside the glass-and-steel cages of our culture, and slow down long enough to hear the birds, see the hearts, and touch the kingdom that is so often hidden in plain sight.

With love and warmth from Rebekah, our six little travelers, and me—

Asahel Adams