What Makes for Peace

Masada fell—but the Church didn’t. One was built by fear, the other by faith. Jesus wept not for Israel’s weakness, but for her blindness. Peace doesn’t come by revolt, but by surrender. And still today, many miss the hour of their visitation.

Reflections from My Final Day in Israel

Setting Out South

After a week in the north of Israel alive with the richness of God’s Word—marked by corporate worship, shared meals, and deep fellowship—we loaded into Brother Daniel’s Hyundai van on our last day and headed south. For me, this would be a day of firsts: a visit to the Qumran caves, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, and then on to the ancient fortress of Masada.

It’s astounding to consider how God, in His providence, used even the misguided zeal of the Essenes—a separatist Jewish sect who withdrew into the Judean desert seeking ritual purity—to preserve sacred manuscripts for generations yet unborn. Believing the end of the age was near, they meticulously copied the Hebrew Scriptures, along with their own commentaries and writings, storing them in clay jars and hiding them in remote limestone caves carved into the cliffs above Qumran, near the Dead Sea. There they remained—sealed, forgotten, untouched for nearly two thousand years.

Then in 1947, a young Bedouin shepherd boy, searching for a stray goat, hurled a rock into a dark crevice high in the cliffs. He heard the sound of breaking pottery. Inside the cave, he discovered the greatest archaeological find in history: ancient scrolls, carefully wrapped and astonishingly preserved. That single discovery led to the excavation of eleven nearby caves, eventually yielding over 900 manuscripts and more than 6,000 fragments—including portions of every book of the Old Testament except Esther. Among them was a near-complete scroll of Isaiah, dated a thousand years earlier than any previously known manuscript.

The Road to Masada

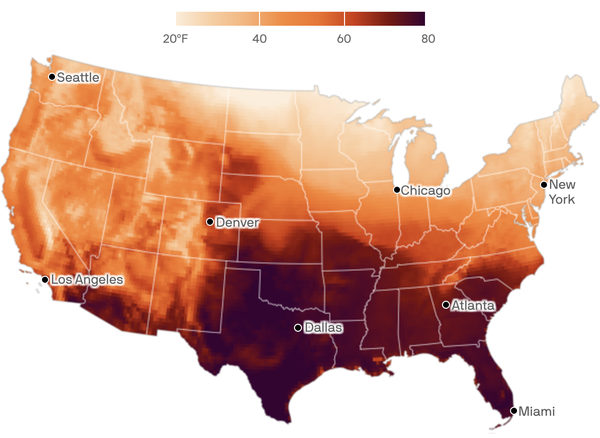

As we wound our way south through the arid Judean desert, skirting the glassy edge of the Dead Sea, the landscape grew starker, more severe. Jagged cliffs rose from the sand, their sun-scorched faces etched with time. The air rippled with heat, and the desolation was complete—no trees, no shade, just rock and sky. It was into this forbidding wilderness that we pressed on, toward Masada.

I didn’t know quite what to expect. A national park, perhaps. A pile of ruins. A tragic tale vaguely remembered from history lessons. But as we stood at the base of the mountain and boarded the cable car, slowly ascending thousands of feet above the desert floor, a different reality began to unfold. At the summit, stretched across the sprawling plateau, were the remnants of an entire fortress complex—walls, storerooms, bathhouses, a synagogue, even a palace. It was a stronghold fit for a thousand souls, perched defiantly above the wasteland.

Herod the Great had built it all—paranoid, powerful Herod. Here, he stockpiled grain, weapons, and water in anticipation of siege—whether from Rome or from his own people. His architectural imprint still clings to the stones: storerooms aligned in neat rows, vast cisterns carved into the rock capable of holding millions of gallons of water—every drop hauled in by donkey, carried jar by jar through the desert heat. A man obsessed with control and survival had left behind a monument to human ingenuity… and to human fear.

Masada is breathtaking. But it is also unsettling. The brilliance is matched only by the madness. It is, in a sense, a monument to hubris—what man can build when driven by dread instead of devotion.

The Siege and the Tragedy

But Herod’s paranoia was not the final chapter written on this wind-scoured mesa.

A century later, around 73 A.D., Masada became the final refuge of nearly a thousand Jewish men, women, and children—survivors of the Roman siege on Jerusalem, where Titus had razed the temple and crushed the revolt with brutal efficiency. These last rebels—families, not just fighters—fled east into the harshest terrain, clinging to the hope of freedom atop a dead king’s fortress.

But Rome followed.

Legionaries marched deep into the Judean desert and laid siege to the mountain. Surrounded on all sides by sheer cliffs, Masada should have been impenetrable. But the Romans, relentless and calculating, built a circumvallation around the entire base—blocking any chance of escape. Then, methodically, they began the assault.

Catapults hurled massive stones toward the walls. When the reinforced barricades held, they switched to incendiaries—pitch-soaked torches launched high into the desert winds. At first, the gusts turned against them, threatening to ignite their own siege engines. But then, as Josephus records, “Providence turned the wind.” The flames surged forward, lapping at the fortress gates, until at last the breach was made.

That night, the rebels knew: at dawn, Rome would ascend. The end had come.

In one of the darkest decisions in Jewish history, they chose mass suicide over Roman slavery. Names were inscribed on broken pottery shards, drawn by lot. Selected men carried out the unthinkable—killing their own families, then each other. When the Romans entered the fortress at daybreak, they found silence—an eerie, haunting stillness. Nearly every soul had perished, save for two women and five children hiding in a cistern, left to tell the story.

Jesus and the Things That Make for Peace

As I walked those dry streets and crumbled corridors atop Masada, I didn’t feel triumph. I felt grief.

Israel today has turned Masada into a symbol of national heroism—a monument to resistance, a rallying cry: “Masada shall not fall again.” But as I stood among the ruins, what echoed in my heart were not the cries of rebels but the tears of a Rabbi—Jesus, standing centuries earlier on the Mount of Olives, overlooking Jerusalem, weeping.

“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem… if you, even you, had known on this day the things that make for peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes.”

He was not indifferent to their suffering under Roman oppression. He knew their pain, their yearning for deliverance. But He also knew that political revolt could not bring them peace. That their enemy was not only Rome—but pride, blindness, and the captivity within their own hearts.

Rome allowed its soldiers to strike a Jew on the right cheek—but only once. Jesus referenced this very ordinance and said, “Turn to him the other also.” Rome could force a man to carry a burden for one mile. Jesus said, “Go with him two.” These weren’t platitudes. They were strategies of a different kingdom—a kingdom not built on revolt but on righteousness, mercy, and self-emptying love.

He was trying to awaken them. To say: Your anguish is not only around you; it is sourced within you. And your deliverance will not come by the sword, but by surrender. Yet they could not see it. As Jesus said in Luke 19:44, “You did not recognize the time of your visitation.”

And so He wept.

He saw, with Spirit-given clarity, what was coming. The siege. The starvation. The fires. The temple burning. The menorah carried off to Rome. He saw Masada. And He wept for their stubbornness. For their zeal without knowledge. For the brutality they would both endure and inflict in the name of freedom.

A Different Kind of Deliverance

They didn’t know what made for their peace. That was the whole tragedy. They couldn’t see that the real anguish wasn’t just around them—it was inside them. The true captivity lived inside their own rib cage.

Jesus saw it. He saw through time, through politics, through zealotry and defiance. He saw the burning city. He saw the trapped families atop Masada. He saw the madness of men trying to secure by blood what could only be received by grace. And He wept.

He wept for their blindness. He wept for their pride. He wept for the carnage they would bring upon themselves while refusing the one path that could have saved them.

Mara bar Serapion, a Roman philosopher from Syria, would later write to his son, reflecting on the downfall of nations that murdered their wisest voices. “The Athenians killed Socrates,” he observed. “The Samians burned Pythagoras. And the Jews executed their ‘wise king.’” In every case, he warned, the judgment that followed was the same: the loss of their kingdom.

Josephus, the Jewish historian who abandoned the rebellion and came to see Roman occupation as the decreed judgment of God—a sentence that had to be endured—records something remarkable. Because of the words of Jesus—His clear warning to flee when they saw Jerusalem surrounded—not a single Christian perished in the siege of the city. While 500,000 Jews were slaughtered in Jerusalem, the early believers had already escaped, fleeing to the caves of Petra. They were not at Masada. They didn’t join the last stand. They didn’t mistake Rome’s retreat as divine deliverance. They saw it for what it was: Vespasian returning to Rome to become emperor, and his son Titus coming to finish the job.

They knew what made for their peace. And they fled.

And here lies the great contrast—Masada was a fortress built on rock. Towering. Isolated. Nearly impregnable. And yet, the gates of violence, of fire and steel, of death and the grave, did prevail against it. It fell.

But the Church—Jesus’ city on a hill—was built on a different Rock. “On this rock I will build My church,” He said, “and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” And they haven’t. No sword, no Colosseum, no massacre, no catacomb, no empire, no tyranny, no flame has ever overcome it. The Church is only defeated when she consents—when she trades her cross for comfort and gives herself to the embrace of a false lover: the world. God has not called His people to defend a mountain that can be touched—a mountain of blazing fire and darkness and storm—but called them to Mount Zion, to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem.

A kingdom not built by hands, and one that cannot be shaken.

Not to Miss the Hour

God, help us.

Help us to know what makes for our peace. Help us to say—not in pious routine but with desperate clarity—“Blessed is the Lamb of God who comes in the name of the Lord.”

Free us from the madness of man’s solutions—from the myth that we can engineer peace through pride, through violence, through stubborn defiance. Free Your children from the delusion that we can save ourselves by winning wars, stockpiling provisions, or building our own modern-day fortresses.

Free us from the captivity inside our own rib cage.

Deliver us from the deafness that ignores the Righteous One—weeping on the Mount of Olives, cleansing the temple, healing the sick—while chalking it all up as a distraction from the real political cause, the real fight, the one we believe we must win. How many today, like the zealots of old, are so infatuated with the cause that they miss the Christ?

Lord, free us from the tragedy of missing the time of our visitation.

May the zealous Christians of today and tomorrow still hear the voice of the One who weeps—for cities, for people, for us—and turn from everything that can be shaken while there is yet time.