Where the Music Stopped

The music stopped, but the story didn’t. Among the ashes of Nova, love endured, courage rose, and hope whispered through charred steel and glass roses: evil may burn, but it cannot erase the image of God—or the light named Ori.

Bearing Witness at Nova

Every time I arrive at Ben Gurion Airport in Israel, something rises in my chest. It happens without fail. The airport corridor swallows you whole, its walls etched with ancient papyrus motifs, reminding every traveler that this land is older than memory. Then, as you spill into the arrivals atrium, the atmosphere shifts. Orthodox families in black garb. Young men in yarmulkes. Women in headscarves. Soldiers in olive fatigues. There are tears, embraces, the smell of strong coffee. But there’s something else in the air—thicker than scent, deeper than sound. Memory. Identity. Survival. Family.

We had come for a conference. But the day after arriving, our dear friend and local guide, Tsafrir, asked if we wanted to go south—to bear witness. To see what had happened.

Two hours after leaving the hill country of Ephraim, we turned off a gravel road and passed through a wire gate. The site looked almost unremarkable at first. Quiet. Bleak. Then the silence unfolded into a kind of cry. We stepped out into a half-circle of charred metal—hundreds of burned cars stacked four and five high, twisted like bones, blackened like coals. Steel frozen mid-scream.

But these weren’t just vehicles. They were testimonies.

On October 7, 2023, thousands of young people had gathered in the desert near Kibbutz Re’im for the Nova Music Festival. It was meant to be a night of revelry—music, dance, and drink. Then, at dawn, they came. Six thousand Hamas terrorists breached the border on motorbikes and in trucks. They opened fire on unarmed civilians, fired RPGs into shelters and ambulances, raped, tortured, mutilated. They didn’t just kill—they desecrated.

The dance floor had become a mass grave.

There are no billboards here. No signs. Just the wreckage of what was—a sculpture of silence. The cars are riddled with bullet holes. Windows shattered. Paint blistered off. Some burned at temperatures over 3,000 degrees Celsius—hot enough to erase license plates, to melt engine blocks. In many of these vehicles, those inside were not only killed. They were incinerated.

Noga met us at the site. A woman in her early sixties, short, steady-eyed, long brown hair streaked with gray. She wore a gauzy shawl and carried herself like someone who had walked through fire—and survived.

She didn’t offer pleasantries.

“Let’s go straight to October 7,” she said.

And we did.

“There were 1,562 cars brought here,” she told us. “More than 800 from the Nova Festival. Two hundred seventy-two of them burned so completely, we couldn’t even identify who was inside.”

She turned and motioned behind her.

“When was the last time Jewish people were burned like this?” she asked.

No one answered.

In the immediate hours after the massacre, ZAKA volunteers—the ultra-Orthodox emergency burial society—arrived on the scene. They didn’t just gather bodies. They collected fragments—bone shards, teeth, blood-soaked cloth, wallets scorched beyond recognition. In Jewish tradition, even a garment soaked in a person’s blood must be buried with them. But there were no names. Only questions.

Who owned this car? Who was driving? Was anyone else inside?

With identifying markers melted, investigators had to trace the partial remains of VINs, scour missing persons lists, and make impossible calls.

“Was your son at the festival?”

“Did your daughter drive a red Toyota?”

“Who was she with?”

Families waited. Not days—weeks. Because it had to be right. Every identification was an act of sacred responsibility.

Some dashcams had survived the heat. From their footage, authorities pieced together faces of the attackers, images of terror, audio of screams. And when machines could no longer help, archaeologists were called in. They could tell the difference between human bone and melted metal. A piece of skull meant death. A bone from a foot did not. These were the brutal lines drawn between hope and finality.

Even nature joined the search.

Bird watchers had long tagged scavenger birds—eagles, hawks, and vultures—with GPS trackers. After October 7, the birds began circling again and again over certain stretches of land. Investigators followed. In those spots, they found the missing.

At one such site, now marked by a weathered wooden sign, they found a soldier. His body had been desecrated. Mutilated. His head removed.

This was not war. It was butchery.

This was not an attack. It was a pogrom.

Every scorched car, every singed wallet, every fragment of cloth is now a vigil, whispering not only of horror, but of the sacredness of life. Of the need to remember. Of the price of forgetting.

Noga told us of a woman who came to her one day, asking if she could search for a small Tehillim—a book of Psalms. Her cousin had been murdered in the attack. In the moments of terror, someone in the car had pulled out the Psalms to pray. During the chaos, it was lost.

She gave Noga the car number.

Later, they found it. A tiny, scorched book. Worthless in the marketplace. Priceless in meaning. A fragment of faith, surviving the fire.

Initially, there was talk of burying the cars—1,500 twisted wrecks scorched into silence. But environmental officials intervened. The heat had fused steel with human remains. The earth itself was now a burial ground. Burying the cars would risk contamination.

So the soldiers found another way.

They cut off the roofs and vacuumed the interiors. Not for debris. Not for evidence. For ash.

Not soil.

Not gravel.

Human ash.

For weeks they worked, reverently collecting what remained—what couldn’t be named or claimed. Three to four hundred containers were filled. These now lie together in a kever achim—a “brotherhood grave”—a place for those whose names were lost to the fire, but not to God or the memory of this nation-family.

If even one bone fragment could be matched, that person was buried with their name. But many who died together—fused in the fire, inseparable in death—were buried together.

We followed Noga to a small blue car. The paint was faded, the interior burned out. The doors clung loosely to their hinges, the frame slumped in on itself.

“This one,” she said softly, “belonged to Ori. In Hebrew, his name means my light.”

Ori had come to the Nova Festival alone. But that night—October 6—he met new friends: Maya, Omer, and a young Thai man named Reg. When the gunfire began the next morning, Ori managed to escape.

But then—he went back.

He returned, into the heart of the slaughter, to rescue the friends he had just met hours before. He found them. All three. They fled together. But they were intercepted. All four were taken hostage into Gaza.

Maya would live to tell the story.

She and Ori were brought to Gaza’s largest hospital—Shifa. But there was no healing there. Under the mask of medicine, no bandages were offered. No IVs. No antibiotics. No pain relief. Only cruelty.

Maya had been shot. Her leg was shattered. The Hamas operatives overseeing her “care” ordered a crude procedure—her leg bones were reset in the wrong direction.

“A backwards surgery,” she said. “Absurd. Painful. Wrong.”

Next to her, lying on a mattress on the floor, was Ori.

He had also been shot—his back pierced with bullets. He was pale. Fading. Untreated. Unseen.

“He just lay there,” Maya said. “No one touched him. No one cared.”

She looked at him, trying to understand how he was still breathing.

“How are you holding on?” she asked. “How are you surviving this?”

Ori turned his head and whispered something she would carry for the rest of her life:

“I’m trying to stay alive for my mother. She’s strong. Like a lioness. Brave. I know she’s out there, fighting. So I have to fight too.”

That night, the curtain was drawn. The next morning, Ori was gone.

When Maya was released and returned to Israel, she asked to meet Ori’s parents. She told them everything—every word, every wound.

His mother sat silent at first. Then she began to weep.

And finally, she said:

“Maya… I was broken. I wasn’t brave. I had no strength. I didn’t want to live. I even thought… maybe it would be better to disappear. But now—hearing this— Hearing that my son believed in me, That he lived as long as he could because of me… Now I will rise. Now I will become the mother he saw in me. I will carry his name. I will carry his story. I will speak—so the world will never forget who he was.”

That was the moment that undid all of us visiting that day.

Not the burned cars.

Not the twisted steel.

Not the ash.

This.

A son who died believing in his mother.

And a mother who rose because her son believed.

Life, in the center of death.

Hope, in a field of horror.

Light, named Ori, in the middle of smoke and silence.

Nearby, there was a white car.

Inside it, thirteen retirees from the city of Sderot died. They were trying to evacuate when their vehicle got a flat tire. They reached a public bomb shelter. Salvation seemed only steps away.

But the door didn’t open.

The city had recently upgraded its shelters with a remote-lock system, controlled from a central command center. In every test, the system worked flawlessly.

But on October 7, when the woman monitoring the cameras saw terrorists entering the city—she panicked. She ran.

And no one opened the door.

Thirteen elderly citizens—neighbors, friends, survivors of past wars—were gunned down in front of a shelter built to protect them.

Locked out. Left behind.

Then there was the ambulance.

Eighteen people had hidden inside—beneath the music stage, behind the scaffolding, crammed into the vehicle’s narrow walls. A desperate last refuge. But the terrorists found them.

They opened fire.

Then they threw grenades.

Then came the RPG.

The ambulance flipped. Caught fire. Bodies melted together.

Among them was Shani Gabay. She took refuge in the ambulance, already wounded and shot twice. She had helped others escape, but ran back to Nova, hoping for a way out. She called her father.

“I’m here. Come get me.”

He came.

But when he arrived, the ambulance was already a pyre. There was nothing left to rescue.

Forty-eight days later, they found her necklace.

DNA confirmed it—three teeth, a few bones.

They buried her.

We left the car graveyard in silence, our thoughts smoldering like the blackened steel we had just walked among. Down the road, Tsafrir pulled over near a sweeping orchard of olive trees. A sudden change in landscape—serene, even sacred. The wind moved gently through the gnarled branches. Some of these trees were young. Others were ancient.

One tree, in particular, caught Tsafrir’s eye.

It looked dead. Hollowed. Charred.

A closer look revealed the truth: a rocket had struck the tree dead-center, splitting it down the trunk, scorching it to black. It should not have survived. And yet—

From around its base, green shoots were sprouting. New life.

There it was: resurrection.

There is hope for a tree… though it be struck and split, yet with water and time, it will rise again.

We drove on toward the Nova site itself—the place where the concert had unfolded.

“This road,” said Hoshea, our friend and a local resident, “is called Death Avenue now.”

Terrorists, dressed in stolen IDF uniforms, had staged fake checkpoints. From the brush on either side of the road, they had opened fire on vehicle after vehicle. The line of cars—each containing the dead—stretched as far as the eye could see.

“Interestingly,” Hoshea added, “these two kibbutzim just over the hill were almost untouched. It was Sabbath. Their gates were locked. Too inconvenient for the terrorists. So they moved on—to easier targets.”

All along the road stood concrete structures—bomb shelters. Reinforced bunkers meant to shield travelers from rocket fire.

But Israel had prepared for missiles, not men.

These shelters had no doors. No locks. No defense against intruders. When people panicked and fled into them, thinking they had found safety, grenades were tossed inside. In an instant, those bunkers became coffins—sealed and silent.

They’re known now as the Shelters of Death.

We pulled off the highway and into the grassy knolls of the Nova Festival grounds.

Hoshea gestured toward a rusting dumpster just off the path.

“That,” he said, “is where scores of people tried to hide. They thought it might save them. But the terrorists found them. Threw grenades in through the lid.”

A small ditch ran between the field and the road.

Many fled that way, thinking they could escape. But their low-riding cars got stuck—bogged down in the dirt, unable to cross. Sitting ducks for the killers who descended the highway from Gaza.

Then Hoshea pointed toward the ravines and creek beds beyond.

“That’s where they ran. Young women, especially—ran into those gulches, thinking they could hide. Some curled into crevices in the dirt walls.”

But the pursuit continued.

They were dragged out.

Ravaged. Brutalized. Shot point-blank.

Others were taken alive—into Gaza.

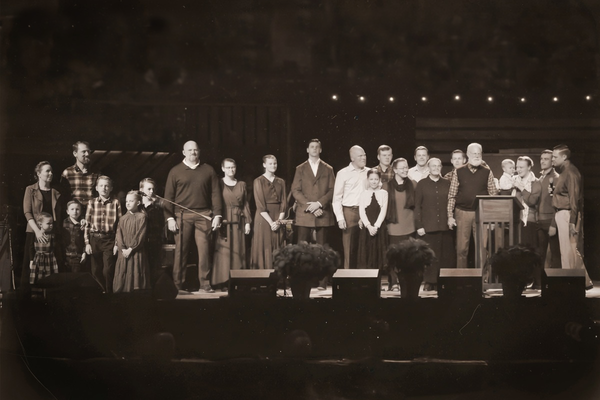

At last, we arrived at the site of the main stage.

It still stood.

But instead of music, there was silence. Instead of dancing, only mourning.

Where thousands once gathered in joy, there were now hundreds of black stakes, pounded into the earth. On each one, a large photograph. The face of someone murdered.

Smiling young men. Beautiful women. Friends. Sisters. Sons. Lovers.

At the base of each post lay glass roses—a fragile tribute to lives shattered.

The wind moved gently through them, like a breath, a lament.

As we stood among the stakes, reading the story of one departed soul after another—Shani, Daniel, Or—one of our companions spoke up.

“That morning,” Daniel said, “I heard screaming. It came from the house across the street. I thought… maybe it was a domestic fight. Loud. Strange. But then—moments later—I saw my neighbor run from the house, jump into his car, and tear out of the driveway.”

Daniel didn’t know what was happening. Not yet. The world hadn’t heard. The headlines hadn’t broken. Only later would he learn: that man’s daughter*—Shani Gabay—*had been at Nova. And her parents had just found out.

“Her dad was gone for three days,” Daniel continued. “Hospitals, checkpoints, calling everyone he knew.

“‘Have you seen her?’

“‘Did she survive?’

“‘Was she taken to Gaza?’”

Then, hope—cruel hope. A photo surfaced. She was bandaged, wounded, but alive, sitting in one of the roadside shelters. They clung to it.

And then—nothing.

No word. No trace. Silence.

Weeks passed.

And then came the truth.

She had been placed in the ambulance. The one targeted with an RPG. The one that flipped and burned, its passengers fused together in flame.

At first, a DNA error delayed confirmation. Her name wasn’t on any list. The family waited, tormented by ambiguity.

Eventually, a grave was exhumed. Inside, they found fragments. Enough to confirm what her parents feared—but had not known.

Daniel paused. His voice quieter now.

“Her mother’s face changed after that. Her body changed. It’s like the trauma didn’t just break her… it reshaped her.”

For 47 days, they believed she was alive in Gaza.

But the truth was worse.

She had died right here. On this ground.

Then Tsafrir shared one last story.

He spoke of a first responder—not someone in headlines, not a name printed on posters or shouted from podiums. Just a man who had said yes.

It was a Jewish holiday. A friend—another responder—had asked him,

“Can you take my shift? I want to be with my family.”

He agreed.

He came to the Nova site. He did his duty. And when the rockets began—when the screaming and shooting started—his superior turned to him and said:

“Let’s go. We won’t make it out alive.”

But he stayed.

“He helped others,” Tsafrir said. “And then he was murdered with the rest.”

Forty days later, his body was returned in a sealed coffin.

And only later did anyone discover:

He was a Muslim Arab Israeli.

He had taken the place of a Jewish friend.

He had died saving Jewish lives.

“We know his family now,” Tsafrir said. “We visit them. Every time I’m here, I take a picture and send it to them. Just so they know—we remember.”

In a field full of rust and ruin, these were the stories still alive.

We left in silence.

Behind us stood the black stakes and the empty concert stage, encircled by rows of photographs and glass roses—each one whispering names. Telling stories. Testifying.

Testifying to the shock of genocidal hatred.

To the frailty of human existence.

And to the beauty of love in the face of evil.

As we turned one last time, I saw a small group of Orthodox Jews gathered near the stage. They swayed gently in a circle, voices rising in a mournful, rhythmic moan—a prayer so ancient it echoed through the Torah, through the prophets, through the Psalms of David. A sound deeper than words.

I thought of Jesus weeping over Jerusalem—grieving the peace they did not know.

And I knew, as we had already seen, that even amidst this horror, love endures, and hope returns, and new life rises—as God’s harassed and hated children begin to discover what truly makes for their peace.

This is the field where the dancing was cut short.

And yet, even now—even in ashes—hope is calling.